The Unoccupied Aircraft Systems Applications and Operations in Environmental Science three-course sequence kicked off in October, beginning with the course Introduction to Unoccupied Aircraft Systems (UAS) in Biology, Ecology, and Conservation. Led by David W. Johnston, Associate Professor of the Practice of Marine Conservation & Ecology in the Nicholas School of the Environment and the Director of the Marine Robotics and Remote Sensing (MaRRS) Lab at the Duke Marine Laboratory, the course focuses on how drones can be applied in biological, ecological and conservation research. Targeted toward research professionals, the end goal of the course is to demonstrate how drones can be applied to learners’ research. The introductory course familiarizes learners with drone platforms, sensors and their uses; flight concepts for fixed wing and rotary wing aircraft; and basic operational considerations, in addition to the legal and ethical implications of drone technology and fundamental best practices around their use.

We employed gamification in the course Introduction to UAS to meaningfully engage students. That is, this course was purposefully designed to incorporate elements of games and encourage play as a form of learning. With research on gamified education to ground the course, Introduction to UAS incorporates games both into the structure of the course through Discord and course activities, including interactive fiction games (similar to books like the Choose Your Own Adventure series or, more recently, Netflix’s Bandersnatch) built for the course using Twine.

Johnston explained his initial reasoning for using gamification, “I think games help people understand the world. I think they help people grow, they help people engage in complex situations and learn how to navigate them — and I think they’re ideal for the kind of thing we’re trying to do here.”

Twine is a simple open-source software that has a low barrier to entry for users — great for creating games based on real-world scenarios that incorporate decision-making. Interactive fiction offers learners the opportunity to navigate a narrated scenario, making choices along the way that influence the final outcome. In the case of Introduction to UAS, learners might successfully use a drone to gather data on a population of nesting birds … or cause them to abandon their nests by choosing a drone that looks too much like a large bird of prey.

“The Twine games were fundamentally exciting for me because they reminded me of those Choose Your Own Adventure Books I read as a kid where you were entertained, but you also learned what not to do,” Johnston said. “And, for some topics, I think learning through narrative this way is so much better than simply asking people to answer questions on a quiz.”

Yugees Rao, a member of the Wildlife Conservation Society, Malaysia Program team, and course participant said she appreciated this departure from previous experiences: “For me, online learning has always been a challenge … Most online learning goes like this: watch a video, do multiple options quiz and then submit for scores. But in this course, the Twine game actually challenged me to think and use what I learned in the videos when facing real world problems. Plus, the explanation for the wrong selections really helped me to understand better. I don’t see this in most quizzes.”

Using Twine to Create Custom Games

Twine has been used throughout courses in higher education both to create assignments for students and to encourage students to create their own games. Some examples include writing, strategic management, pharmacy, and English. Introduction to UAS provides an example of using interactive fiction to teach environmental science.

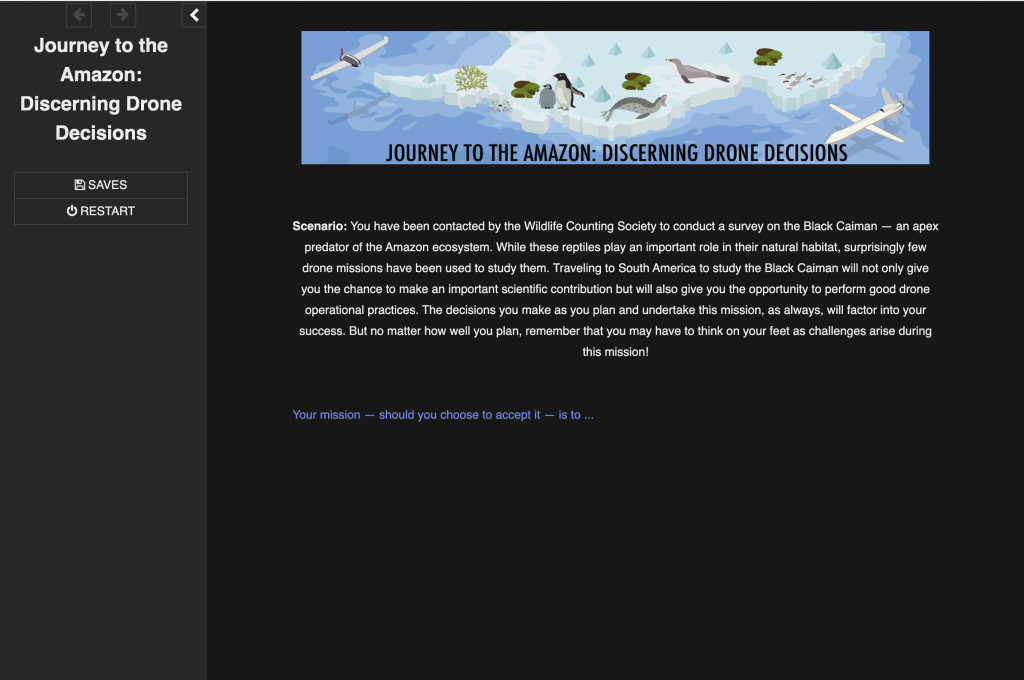

Throughout the course, students play three different Twine games that cover: possible pitfalls for drone pilots; opportunities to practice decision-making skills in mission planning and multiple use cases of drones in the fields of biology, ecology and conservation. Spread strategically over the six-week course, Johnston envisions these games as building upon one another, allowing learners to apply what they’ve learned in course videos, readings and discussions to a real-world scenario.

“I feel like the Twine games are really this super cool intersection of … a pop cultural sort of thing and an entertaining way to draw people into complex situations and ask them to learn by doing,” Johnston said, noting in his lab one of fundamental things the team does is frequently pause and ask ‘what could go wrong here?’ Johnston sees the Twine as teaching learners to think this way. “It’s a really healthy way to think about training people for this kind of work.”

To build these games, the Introduction to UAS team brainstormed a wide-array of scenarios to give learners experience thinking about different climates, species and mission types, as well as considerations they would need to take into account, including legal and ethical standards. The scenarios for the Twine games drew on Johnston’s Lab’s experiences in the field, recent research examples and other sources (e.g., U.S. drone regulations).

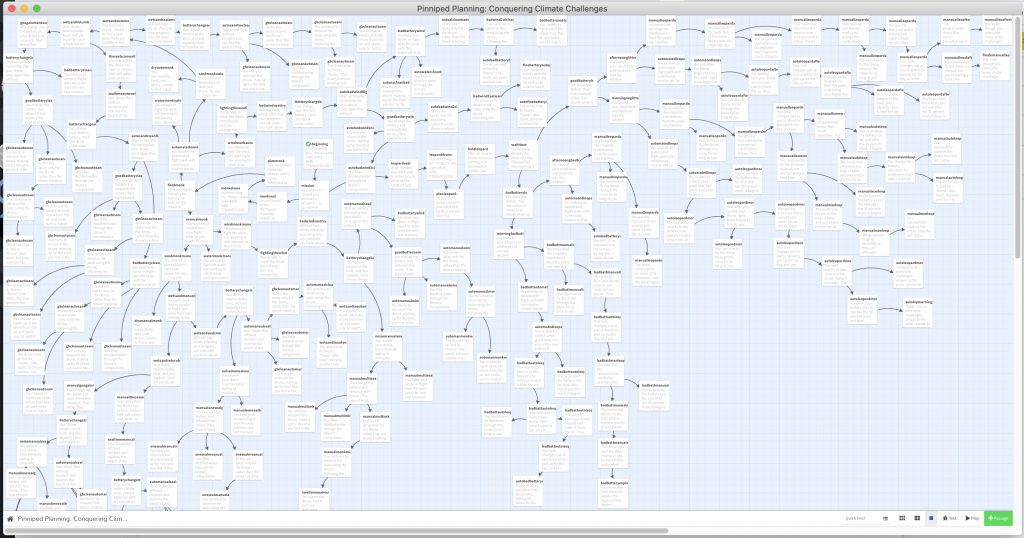

Once the scenarios had been created, the team made decisions about where paths would diverge, how this would test student knowledge and what students would learn from each “success” and “failure.” After prototypes of each game were built, they underwent multiple rounds of playtesting and were revised for clarity and accuracy.

This work paid off, giving learners of different experience levels, knowledge bases and interests the opportunity to think through missions.

“I have never used a drone or worked with marine animals. The Twine game was really informative and I got to learn a lot about things I would never ‘get my hands on’ otherwise,” Rao said.

Fellow course participant Rachel Brewton, Research Scientist & Geosciences part-time PhD student at FAU Harbor Branch, shared Rao’s sentiment, “The choose your own adventure is like hands-on learning without having to actually crash a drone or accidentally harass wildlife. I think I’ll be much better prepared, situationally aware and ready when I actually start to venture out with my drone.”

The Twine games also helped learners prepare to conduct similar missions in reality. The final Twine game of the course, for example, featured a mission focused on surveying the Black Caiman, which was particularly helpful to Lonnie McCaskill of the Wildlife Conservation Society.

McCaskill said, “I really enjoyed this, and it may have real life implications for my work directly, as I’ve been asked to do Black Caiman work in the future with a number of Latin American field biologists. [This] really made me more aware of all of the t’s needing to be crossed and i’s dotted before moving forward … I really liked the Twine games that made you think critically about what you would do in real time conditions for the information you were trying to collect or scope of missions.”

How You Can Use Twine in Your Own Course

Interested in using Twine to create your own educational games? There are many resources online to help you get started. For instance, the Duke Game Lab hosted an introductory Twine workshop in Spring 2020 and has posted a recording of that event. If you’re using the story format SugarCube, there are multiple introductory tutorials on YouTube as well.

Here are some tips to keep in mind when considering if Twine is right for you:

- Consider your time constraints, and budget your time. Do you have the time to learn a new tool (and perhaps some simple HTML)? If so, do you have time to write and create the games themselves (some might take between 10-30 hours total)? Will you have the team to perform quality assurance tests and make adjustments? Does the outcome of your Twine game justify the time you will put into it? Will you be able to reuse these in the future?

- When designing your Twine game, ensure it aligns with specific course or unit learning outcomes. How does this game align with your goals as an instructor? What will students uniquely get out of this experience? How does this fit with the overarching design of your course?

- How does gamified learning fit with your course? Is there a natural connection between the course content and games or play? Are you planning to gamify the course beyond Twine games? Will these choices make sense to learners?

If you choose to use Twine, you should keep accessibility standards in mind while designing your game. The SugarCube story format has been recommended for accessibility purposes, as it includes some built-in accessibility support. The Interactive Fiction Technology Foundation conducted an accessibility survey in 2019 of interactive fiction games made in platforms such as Twine and produced the 2019 Accessibility Testing Report, which includes considerations designers should take into account to make their games more accessible. Discussion of Twine and accessibility has taken place on the Twine subreddit, which also provides further help to users.

Completed Twine games can be exported as HTML files. Our team found that the easiest way to host these games was through uploading them to the course site’s Sakai site in Sakai Resources. Students could then access the games through the Sakai link.

Learn More

To see Twine in action, check out a short demo of the Choose Your Drone … Wisely game from the course.

Want to discuss using Twine in your course? You can email us at learninginnovation@duke.edu if you have questions about whether this is the right technology for you.